|

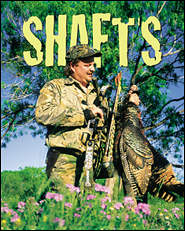

Shafts vs. Shells

Any way you go, whether it's a 12-gauge pump or a high-tech compound bow,

spring turkeys are downright dazzling birds.

By Larry Bozka

Pearsall, Texas, April 2, 1998-Opening

weekend of the South Texas Rio Grande turkey season. A magical

time of yellow-bloomed prickly pear, waving seas of bluebonnets

and a growing sense that the season is turning a fresh new leaf. The air is clean

and brisk, and life is everywhere.

Thirty-year-old Kyle Ward has been

hunting with his father, Ron, as long as he can remember. Kyle

is a bowhunter, one of the most avid archers I've ever met, and

compound in hand he has dropped his share of game--among the lot,

he says modestly, "around 15 deer, 6 of which were bucks."

Last November he arrowed a heavy-racked 12-pointer (a "6-by-6,"

as it's known back home in Wisconsin). But like his dad, a retired

oral surgeon who now spends every possible

day afield, he had never killed a turkey.

Me? I've shot a few. But not this

time.

"I'm gonna be a guide,"

I told my buddies prior to the trip. Every time I said it I couldn't

help but laugh.

Neither could they.

Wild turkeys, you see, are

extremely intelligent birds. They have the eyesight of an eagle,

can discern colors of every imaginable hue, and heaven help you

if you so much as twitch when a big tom is in sight. You move,

he's gone. Wild turkeys, you see, are

extremely intelligent birds. They have the eyesight of an eagle,

can discern colors of every imaginable hue, and heaven help you

if you so much as twitch when a big tom is in sight. You move,

he's gone.

It's long been said that

if wild turkeys had a highly-developed sense of smell, we'd never

kill one. I believe it.

I'd spent weeks practicing

on a Knight & Hale Model 111 "Ole Reliable" Double

Mouth Diaphragm call ("Great for the beginner, as well as

the advanced caller," the packaging read). The best time

to practice, I discovered, was while driving the 55 miles of Beltway

8 between my home in Seabrook and the Texas Fish & Game office

off Hwy. 290 in northwest Houston. In retrospect, I'm surprised

some of the toll booth ladies didn't dial 911 to report some loony

in a green Durango making obscene noises.

Anyway, I got better and

the season drew closer. Next thing I knew Ron, Kyle and I were

opening the gate to Bill and Bobbie Ingram's Rock House Ranch

in Frio County. We were invited guests; no commercial turkey hunting

is done here. Which, given my degree of expertise at turkey calling,

sounded absolutely wonderful. No wild turkey is stupid, but these

birds were at least relatively uneducated.

We arrived a little after

lunchtime, chowed down some sandwiches with our hosts Macky McIntyre

and ranch manager/biologist Ross Eckhardt and hit the field. A

small, narrow creek intersected the road, fringed by a thick curtain

of mesquite and oak trees that, according to Eckhardt, were serving

as roosts for several groups of birds.

Ron and I headed upstream;

McIntyre and Kyle went the opposite way. I slammed the truck door-a

tactic that, like blowing a screech owl "hooter" or

a woodpecker call-normally gets 'em gobbling. Nothing but silence.

So we slowly walked toward the rising sun, looking closely for

any sign of birds. There were, however, no tracks. And still,

no sounds. I blew the "hooter" again. Again, no response.

We set up on the western

side of a large, freshly-plowed field. I planted a pair of dekes-an

Outlaw jake-and-hen combo-while Ron climbed up a tripod stand

immediately above the brushpile I'd hunkered into. It was unusually

hot, and the mosquitoes were raging. After about 45 minutes of

calling, waiting and sweating, I looked up toward Ron.

"What do you think?"

I asked.

"Pretty slow,"

he answered.

"Let's move. We're sure

not doing any good here."

I packed the decoys into

the mesh backpack. Ron climbed down from the tripod and we edged

closer to the hardwood creekbottom. "You thought the mosquitoes

were bad back there?" I asked. Ward wiped a bit of mosquito

blood-make that his blood-from his sweat-beaded face and nodded

his head.

Ron Ward is a personable

fellow, but when he hits the field he turns into a focused hunter.

The non-responsive birds, coupled with miserably hot weather,

the relentless mosquitoes and a wannabe "guide" who

had never before called in a turkey, had no doubt made him feel

somewhat pessimistic about the whole deal.

To be honest, so did I. So,

I shut up and followed Ward's hand signal to move farther uphill,

where we slowed down the pace and stalked through the senderos

between the dense thickets of mesquite and live oak. "I was

pretty much convinced that the birds-assuming they were even there-were

less than enthusiastic about your calling," he later admitted.

That's one of the things I truly appreciate about Ron Ward. The

man says what's on his mind, and rookie that I am, I was certainly

in no position to disagree.

We turned a corner, headed

back to the west and-just as we were about to round a treeline

bend, simultaneously spotted several gobblers ambling about around

200 yards away in the fading evening light on the same side of

the brushline we were skirting. In unison, we stopped in our tracks.

"I remember it vividly,"

Ward said that night around the campfire. "I got in front

of you, and moved back in the brush. Positioned like that, neither

one of us could see a danged thing."

I remembered it well, too.

There was no way I could move out into the open and set the decoys

in place without being spotted, so I stuck them in the ground

just a few yards from the edge and backed into the underbrush.

Moments later, I heard clucking.

"You started out with

the box call, clucking a 'putting' kind of noise, and I thought

to myself: What is he doing? I'd never heard such a thing. You

kept telling me that you could hear the birds, but I couldn't

hear a thing, and I sure couldn't see anything. I didn't have

a clue what was going on."

I didn't, either. No matter

how I worked that box call, the tom wouldn't talk to me. So, I

popped "Ole Reliable" into my mouth, made a feeble

attempt at a "kee-kee run" and the bird sounded off

like a noontime factory alarm. A nanosecond later, I was shaking

uncontrollably.

It was totally unnerving.

I couldn't see anything, either, but at least Ron was ahead, between

me and the incoming gobbler with the decoys about 10 yards to

my right. I hoped-make that prayed-that the bird would spot the

decoys and move on in.

"I still couldn't see

him," Ward continued, "but it was obvious that he was

getting closer. He couldn't have been much more than 50 yards

away at that point. It sent a shiver down my spine. You'd tell

me 'I hear something;' you're making this crazy noise behind me,

and I have no idea what the hell it is. When the bird gobbled

back at you, and did it so loudly, I finally realized that something

was going on. I can literally still hear my heart pounding. It

was like, 'We're really doing this!' And it was exhilarating.

continued

page 1 / page 2

|